Description

JOURNEE D’ETUDE – REINECKE EPIGONE ROMANTIQUE

11h – 19h – lieu 78 rue de Rome 75008 PARIS

Code d’accès 5371 – Rez-de-chaussée au fond à droite

11.05 Introduction: Epigonalism as a key to 19th century performance practice and Reinecke’s Recordings – Laura Granero and Sebastian Bausch

Reinecke the Pianist

11.30 Reinecke’s Mozart: Editions, Arrangements and Recordings – Neal Peres da Costa

12.00 Reinecke’s Haydn: Camilla Köhnken, Joseph Haydn Privathochschule Eisenstadt

12:30 Reinecke’s Beethoven: “Susceptibility for Moods and Knowledge of Structure”– Instructions, Metrostyle-Tempos and Recordings as different levels of consciousness in musical performance – Sebastian Bausch

13.00 Who was Mrs. Reinecke?: The four hands recordings of Carl and Margarethe Reinecke – Laura Granero

13.15 – Lunch Break

The Leipzig Tradition

14.30 Introduction: A Reinecke school on early recordings? – Sebastian Bausch

14.45 Reinecke the conductor: The Kapellmeister tradition in Leipzig vs. the new ideal of a Wagnarian conductor – Kai Köpp

15.15 Training the Imagination: character and narrative in mid-19th century instrumental music as seen through the music of Carl Baermann (1811–1885) – Emily Worthington, University of York

15.45 Tea-Break

Performing Reinecke’s music

16.00 Introduction: Reinecke’s music on early recordings – Sebastian Bausch

16.15 Open Rehearsal: Reinecke’s chamber music – Fanny Davies Ensemble

17.15 Break

17.45 Reinecke’s melodramas: The lost connection of declamation and musical performance – João Paixão and Artem Belogurov

18.30 Round Table and Closing Discussion

19.00 End

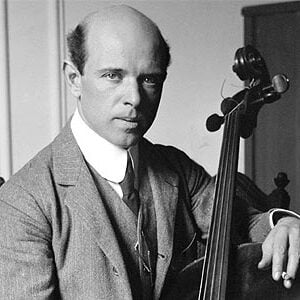

Carl Reinecke à 200 ans :

Pionnier de l’enregistrement et épigone des pratiques d’interprétation du XIXe siècle

Carl Reinecke fut le musicien le plus anciennement né à avoir réalisé des enregistrements.

Ces enregistrements, effectués sur des rouleaux pour pianos reproducteurs entre 1905 et 1907, alors qu’il avait déjà plus de 80 ans, représentent moins la vie musicale de l’époque que le témoignage d’une culture musicale sur le point de disparaître. Reinecke semblait presque revendiquer son statut d’épigone, et c’est peut-être dans cet esprit qu’il a accepté de préserver son jeu pour la postérité. Alors que les enregistrements largement diffusés d’artistes renommés tels que Paderewski, d’Albert et Busoni documentent de manière vivante et détaillée le paysage musical diversifié du fin de siècle, les enregistrements de Reinecke – tout comme ceux du violoniste Joseph Joachim – offrent un aperçu rare du monde musical antérieur de Mendelssohn, Schumann et du milieu du XIXe siècle, qui avait presque disparu au tournant du siècle.

En l’honneur du 200e anniversaire de Reinecke, cette journée d’étude prendra ses enregistrements comme point de départ pour explorer les pratiques d’interprétation académiques allemandes de la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle à travers les traces sonores préservées dans les premiers enregistrements. Les pianistes et chercheurs-interprètes Laura Granero, Sebastian Bausch et Neal Peres Da Costa exploreront la personnalité multifacettes de Reinecke en tant qu’interprète de styles et de compositeurs variés. En tant qu’interprète de Mozart, Reinecke était unanimement respecté et a joué un rôle clé dans la résurrection des concertos pour piano de Mozart en tant que partie intégrante du répertoire standard. Cependant, en tant qu’interprète de Beethoven, il se positionnait comme un adversaire farouche de l’école Liszt-Bülow. À travers ses enregistrements à quatre mains avec sa femme, Reinecke nous offre également un aperçu de la culture de la « Hausmusik » du XIXe siècle.

Kai Köpp et Emily Worthington élargiront la discussion au-delà du piano en recherchant des traces des pratiques d’interprétation parmi les musiciens des orchestres, des cordes et des vents au sein de l’Orchestre du Gewandhaus de Leipzig et du Conservatoire. Malgré la longue carrière de Reinecke en tant que Kapellmeister du Gewandhaus et directeur du Conservatoire, plusieurs facteurs – notamment le système de double enseignement au Conservatoire et son renvoi brutal, remplacé par le wagnérien Arthur Nikisch – compliquent la tâche de retracer et de définir le style d’interprétation instrumentale et d’enseignement à Leipzig au cours de la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle.

La session finale de la journée d’étude se penchera sur ce que signifie interpréter la musique de Reinecke aujourd’hui, en mettant l’accent sur les pratiques d’interprétation historiquement et phonographiquement informées.

En avant-première de leur prochain concert, l’Ensemble Fanny Davies organisera une répétition ouverte de la musique de chambre de Reinecke, invitant les participants à la journée d’étude à participer à une discussion collaborative.

Le lecture-récital de João Paixão et Artem Belogurov mettra en lumière le genre presque oublié du mélodrame, qui est central pour comprendre les esthétiques et les pratiques interprétatives du XIXe siècle, grâce à son lien étroit avec la déclamation et la parole.

Résumé des communications

11.30 Reinecke’s Mozart: De-‘classicising’ the canon – Reimagining Mozart’s K. 488 through dialogues across time Neal Peres da Costa, Sydney Conservatorium of Music

The 20th-century heralded unprecedented change in ‘classical’ music performance aesthetics as documented in sound recordings. By 1950, many unnotated expressive techniques (belonging to a long-established continuum of practice) had been all but expunged. In this ascendant modern style, the notation came to be considered sacrosanct, arguably for the first time ever. Compositions from Bach to Brahms donned identities and sound worlds that largely reflected their notation, largely devoid of individual artistic expression, and increasingly homogenous across performances and recordings. This text-literal ‘classicised’ style remains pervasive, even in historically informed performance (HIP), and has stultified performers and audiences alike.

But innovative methods including: i) emulation/imitation of 19th-century-trained musicians on record; and, ii) cyclical processes in applying historical written evidence, can reignite artistic agency to help unlock the modernist sound of canonic works. This presentation will highlight a novel reading of Mozart’s Piano Concerto K. 488, recorded by me with the Australian Romantic & Classical Orchestra on period instruments. Referencing, among other significant evidence, the ear-opening 1904 piano roll by Carl Reinecke (b. 1824)—lauded as preserver of an ‘old’ Mozart tradition—of his piano solo arrangement of the K. 488 slow movement, we re-enact documented Mozartian practices of note dis-alignment, marked rhythm and tempo variation, and ornamentation. In so doing, we reimagine Mozart as unbridled, blustery, varied, and rhetorical, an alternative to the expected identities for his music of pretty, neat, tidy, and balanced. Such vivification of past musical practices can inspire renewed artistry and expressivity in the staging of classical music.

12.30 Reinecke’s Beethoven: “Susceptibility for Moods and Knowledge of Structure”– Instructions, Metrostyle-Tempos and Recordings as different levels of consciousness in musical performance

Sebastian Bausch, Bern Academy of the Arts

While Beethoven’s music was central to 19th-century discussions of musical interpretation, it occupies a relatively small place within Carl Reinecke’s recorded legacy. Nonetheless, Reinecke’s deep, lifelong engagement with Beethoven is well-documented, particularly in his renowned letters on performing Beethoven’s piano sonatas. In these letters, Reinecke presents the sonatas as a progressive course in interpretation, designed to guide pianists from an intermediate amateur level to the highest professional standards. striking discrepancy, however, exists between Reinecke’s pedagogical texts and editions and his recorded performances. The recent discovery of his “Autograph Metrostyle” piano rolls, created in collaboration with the Aeolian Company in 1904, offers a unique opportunity to bridge this gap. The Metrostyle lines, indicating the intended tempo changes on an otherwise mechanical piano roll, offer an intermediate layer of consciousness and reflection, between the abundance of empirical, but often also unintentional evidence in recordings and the highly reflected and sometimes more abstract instructions (as illustrated in Kai Köpp’s systematic hierarchy of performance sources).

This presentation will introduce a new method for deciphering Metrostyle markings, shedding light on their interpretive implications and limitations.

14.45 Reinecke the conductor: The Kapellmeister tradition in Leipzig vs. the new ideal of a Wagnarian conductor, Kai Köpp, Bern Academy of the Arts

Carl Reinecke’s legacy as a composer as well as a pianist and teacher is accessible through his compositions, editions and recordings. However, Reinecke was also an important conductor who, after positions as music director in Barmen and Breslau, was appointed to the Leipzig Gewandhaus orchestra in 1860. Reinecke must have had a significant influence on orchestral performance practices in Leipzig over the next 35 years. Therefore, it was even more upsetting for him that in 1895, he was replaced by a conductor of almost the opposite style: Arthur Nikisch was an ardent admirer of Wagnerian conducting, that he had already represented 1878-1889 as Kapellmeister of the nearby Leipzig Stadttheater. While there are no recordings of Reinecke conducting, Nikisch famously recorded Beethoven’s 5th symphony in 1913. In my presentation I argue that the performing style of the conservative Berlin Hofoper, that recorded the same symphony three years earlier, would be similar to the Gewandhaus style under Reinecke’s baton. A comparison between these recordings highlights the stylistic differences.

15.15 Training the Imagination: character and narrative in mid-19th century instrumental music as seen through the music of Carl Baermann (1811–1885) – Emily Worthington, University of York

The Baermann’s Body project (2023-2025), funded by the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council, is the first in-depth study of the 19th century clarinetist, instrument designer and pedagogue Carl Baermann (1810-1885). Baermann was the most important clarinetist and teacher of the mid-19th century, leaving a rich body of evidence of a performance practice directly linked to composers including Weber, Mendelssohn, Meyerbeer, Liszt, Schumann and Wagner. While there is as yet no proof of direct contact between Baermann and Reinecke, the congruence of their circles of associates and the similarity of their musical outlooks and personalities makes Baermann the most relevant source of evidence for the performance of Reinecke’s works for clarinet.

This presentation, illustrated by live performance, will explore Baermann’s approach to imagination and musical character with reference to his Vollständige Clarinett-Schule (1860-1864), his compositions for clarinet and piano and his transcriptions of Schubert lieder. Baermann’s detailed indications of breathing, articulation and accentuation tacitly encode a complex, multi-layered approach to phrasing and rubato similar to that observed across the corpus of early recordings (eg Harrison and Slåttebrekk, n. d.). This approach can be understood in relation to the traditions of song and spoken word performance, as well as narrative approaches to instrumental music that were ubiquitous in Baermann’s wider artistic community (Muns 2017, Torbianelli 2014), practices that he enacted through programmatic annotations, descriptive titles and text underlay in his compositions for clarinet. The presentation will conclude with a discussion of the application of a Baermann-inspired narrative approach to the second movement of Reinecke’s Trio op. 274 for Clarinet, Horn and Piano, entitled A Tale.

17.45 Giving Body to the Voice: Carl Reinecke’s Melodramas Acted Out

João Paixão, Amsterdam University and Artem Belogurov, Utrecht Conservatory

The genre of melodrama begins in the second half of the eighteenth century as a pioneering effort to combine the speech and action of an actor experiencing the passions with orchestral music that represents these passions sonically. Throughout the nineteenth century, this once exclusively theatrical genre, gradually found its place on the concert stage. Despite this shift melodrama did not loose its theatricality. On the contrary, the speech, having to compensate for the absence of the theatrical setting, became even more expressive. As Jacqueline Waeber, a noted scholar of melodrama, observes, one of the consequences of nineteenth-century melodrama was ‘mettre la scène dans la voix’ (2005). In this presentation, we will travel upstream and explore the acting that informs the voice in two melodramas by Carl Reinecke. We will examine the connections between tempo and gesture and between emotion and utterance, in an attempt to expand our expressive horizons in this and potentially other genres.

Avis

Il n’y a pas encore d’avis.